In June 2013, I was inveigled by Harper’s Bazaar Art Arabia into flying to Singapore to review a show entitled Terms and Conditions at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM). During my lush sojourn, I met Tan Boon Hui, then Director of the SAM, and head of this year’s Singapore Biennale.

Although Boon Hui has since left the SAM to take on a broader role with the country’s cultural powerhouse, the National Heritage Board, he is still orchestrating the Biennale, which is now about halfway through its four-month stint.

Eminently articulate and wildly enthusiastic about his multiple roles, Boon Hui is at the helm of a Biennale boasting a (relatively) unique curatorial model: 27 different curators officiate over selection and exhibition of works almost entirely by artists linked to South East Asia.

Our interview took place about two months prior to the Biennale’s opening, when proposals were still being hotly debated and loose ends abounded. Everything has since been whipped into shape, and the Biennale is in full swing. So I thought it important to reminisce: here I revisit Boon Hui’s ever-relevant comments on the so-called Global South, the audience-growing power of the biennial format, the multi-curator model and (the bane of many a biennial) censorship.

Our interview took place about two months prior to the Biennale’s opening, when proposals were still being hotly debated and loose ends abounded. Everything has since been whipped into shape, and the Biennale is in full swing. So I thought it important to reminisce: here I revisit Boon Hui’s ever-relevant comments on the so-called Global South, the audience-growing power of the biennial format, the multi-curator model and (the bane of many a biennial) censorship.

Kevin Jones: 2006 saw the first Singapore Biennale. It seemed to be part of a bigger economic thrust, propelled as it was by the vision of Singapore 2006: Global City, World of Opportunities. There was evidently a strategy of linking culture to economic growth. How successful would you say that strategy has been and how has it evolved?

Tan Boon Hui: The 2006 Biennale was almost like a program in an economic congress. The idea was that you couldn’t be an economic global hub if you didn’t also have a cultural dimension. It was an attempt to round off what a global city meant. But it was successful. The 2006 Biennale brought many artists into prominence. It also reached people who would not normally go to museums, who would never be exposed to contemporary art. For most people, art was paintings on a wall or sculpture on a pedestal. The idea of installations, performance, video and audio installation, of art that was tied into the social fabric – all this was very new. The biennial format is useful in a country where culture is developing and you are trying to grow audiences for art: instead of having little flotillas, you suddenly bring out the aircraft carrier. No one can fail to notice it. It was a very important platform to kick-start conversation.

Tan Boon Hui: The 2006 Biennale was almost like a program in an economic congress. The idea was that you couldn’t be an economic global hub if you didn’t also have a cultural dimension. It was an attempt to round off what a global city meant. But it was successful. The 2006 Biennale brought many artists into prominence. It also reached people who would not normally go to museums, who would never be exposed to contemporary art. For most people, art was paintings on a wall or sculpture on a pedestal. The idea of installations, performance, video and audio installation, of art that was tied into the social fabric – all this was very new. The biennial format is useful in a country where culture is developing and you are trying to grow audiences for art: instead of having little flotillas, you suddenly bring out the aircraft carrier. No one can fail to notice it. It was a very important platform to kick-start conversation.

It is actually in line with growing cultural appreciation. Only in 2009 when I came to the SAM did we make the decision to dedicate the whole museum to contemporary art practice. That’s one year after the 2nd Biennale. I think audience awareness of contemporary art had grown considerably. If it weren’t for that, I would never have been able to propose a format like the one for this current Biennale – to have a Biennale that is not afraid to say “I want to be relevant to my region.” I mean relevance in terms of the physical, cultural and social context we are in. Even now, the Biennale is a high point in the contemporary art calendar. Yes, tourists that will come for the Biennale, but this is possible only because of the ambition for culture. Culture has a kind of magnetism.

It is actually in line with growing cultural appreciation. Only in 2009 when I came to the SAM did we make the decision to dedicate the whole museum to contemporary art practice. That’s one year after the 2nd Biennale. I think audience awareness of contemporary art had grown considerably. If it weren’t for that, I would never have been able to propose a format like the one for this current Biennale – to have a Biennale that is not afraid to say “I want to be relevant to my region.” I mean relevance in terms of the physical, cultural and social context we are in. Even now, the Biennale is a high point in the contemporary art calendar. Yes, tourists that will come for the Biennale, but this is possible only because of the ambition for culture. Culture has a kind of magnetism.

KJ: Even when it was a so-called “international” biennial, it still dealt with specifically Asian themes. I am thinking of Phil Collins’ 2011 video The Meaning of Style about Kuala Lumpur skinheads. Elmgreen and Dragset even recontextualized a German barn to Singapore. Does it not seem unfair to exclude the international artists from the Asian roster?

TBH: Having an international biennial does not mean being a United Nations of art, bringing an artist from every point in the globe. You can be international simply by looking at what is special about a particular region, especially as contemporary art has become so globalized. If the art is good, it can speak more about the world, and less about where the artist is from.

We felt very strongly about raising questions of “what is a biennial.” Why are there so many biennials in Asia, for instance? Through this lens, by just looking at the region, we could see echoes. Yes, the Phil Collins work was commissioned last Biennale precisely to look at the local context. But this year it is pushed much further. There is a “compression of perspective” that we expect to be heavier. We think it will be very interesting to see what comes out of there.

KJ: When you say “compression of perspective,” don’t you worry the Biennale could fall into the trap of tunnel vision for a purely Asian identity? As you say, there are so many biennials and it has become somehow trite to just work on that Asian identity, just as it has to harp on about the Arab identity here in the Arab world. The most sophisticated artists, it seems to me, are the ones who go beyond that. Is that something the curators are knowingly working around, or are you just letting it happen organically?

TBH: The debates focus on what it means to look at artists coming from the region as a lens. This idea of geography is itself slightly misleading; there is more variety and diversity in it than people anticipate. For example, we have artists that are ostensibly South East Asian, like a Cambodian artist who is proposing a sound work. He actually lives in the US. He spends very little time in Cambodia. So is he a Cambodian artist? Not really. His proposal questions this idea of what it means to be identified with a locale where people are preoccupied with minimizing the attachment of their identity to any cultural labelling. Think of the lady who recites the airport announcements: her precise preoccupation is to detach her aural identity from any cultural or geographical identification.

One thing became clear very early in preparing this Biennale: there won’t be any country pavilions. The artists are not “tagged” into particularly countries.

KJ: The Biennale themes over the years are very interesting. Belief, Wonder, Open House, If the World Changed... They seem to narrate the neo-liberalist progression of Singapore itself. Is that just my reading, or was that somehow planned?

TBH: Looking back, it was an organic response to people asking “what could it mean for us to have a biennial?” So I don’t think it was deliberate, but at least for this Biennale (If the World Changed…), it sprang from questioning how art relates to a world that many feel is transforming. We are not talking about something concrete, like this war or this climate change, but the whole summation of this and how people feel it. Many of our co-curators, who live in rural, remote communities in South East Asia, will say, “No, the world does not change. Tomorrow will be exactly the same thing.”

TBH: Looking back, it was an organic response to people asking “what could it mean for us to have a biennial?” So I don’t think it was deliberate, but at least for this Biennale (If the World Changed…), it sprang from questioning how art relates to a world that many feel is transforming. We are not talking about something concrete, like this war or this climate change, but the whole summation of this and how people feel it. Many of our co-curators, who live in rural, remote communities in South East Asia, will say, “No, the world does not change. Tomorrow will be exactly the same thing.”

KJ: Looking forward, with all of the questioning going on, would you qualify the Biennale as a space for experimentation in Singapore?

TBH: Yes, particularly because of the artists we have announced. Many of them are not so well known on the international circuit. Their work is very confident and wholly contemporary. There are many levels of newness that are interesting and we are getting a whole range of work from across the spectrum – from spectacular installations to painstaking work that is intense and delicate. People will find the work very surprising.

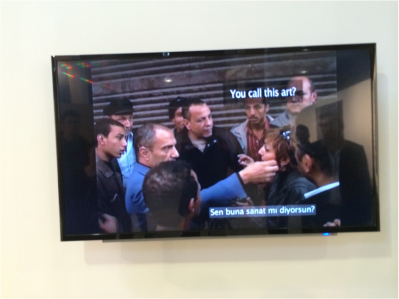

KJ: Censorship is a question that always hounds biennials. You were directly involved in the outcry surrounding Simon Fujiwara’s Welcome to the Hotel Munber in 2011. If the Biennale is going to be a place of experimentation, shouldn’t it have some kind of immunity? Is it not somehow exempt from “normal” rules?

TBH: I would repeat what Sheikha Hoor al-Qasimi said for the Sharjah Biennial in 2011. For Singapore and South East Asia, contemporary art is very, very new; that is the reality. The end objective is to slowly move the fulcrum of public appreciation of contemporary art. I mean art with all its barbs: it is not just pretty, sometimes things hang out, sometimes it’s sharp, it’s a little bit acidic. So the Biennale is a very important platform to build support for contemporary art. It carries that burden. Hence, we would never be completely immune from these considerations. But, each time, we can push the envelope a little further. Actually if you look at the Biennale through the years, each instalment pushes the limits a little bit more. It will take time, but we have learned to act early. The more upstream we go – when commissioning, for example – to already have conversations with the artists, the easier it is to deal with censorship issues in an honest, dignified way that doesn’t damage the artistic integrity of the proposal. We don’t want a situation where you react post-mortem.

KJ: Can you tell me about this commissioning process? Is it any different, given the multi-curatorial approach this year?

TBH: The commissioning process is more or less still the same. At certain points the entire curatorial team gets an opportunity to look at all the proposals and concepts as a whole. This year, with the benefit of such a diverse curatorial team, how individual artworks work with each other becomes more intense and yet nuanced at the same time. These curators know very intimately the stream of work of that particular artist, that trajectory. So you have a much more rounded discussion of how two works have a conversation with each other physically in the space. Or how two works could be together because they absolutely refuse to converse with each other – they are polar opposites, so as a display it works because they confront each other. We are trying to use the tensions that come from this to energize the final exhibition.

KJ: This is the first time I’ve seen a platform of 27 curators going at a biennial. Could you tell me where this idea came from, what is the history of this configuration? How do you foresee it panning out?

TBH: Originally, the idea of curatorial teams, of country experts having deep local knowledge, was launched by the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) in Brisbane. It was a way to build. When you are relatively young and new, you have to build expertise and draw upon the existing knowledge people have of the regions. The first three iterations of the APT in the 90s used this to great effect. I saw value in adapting this approach, with one key difference: we don’t really highlight the artists’ countries of origin.

KJ: Sharjah, Kochi and other biennials outside of the Western circuit are concerned with the idea of the Global South. Sharjah this year made that very explicit, whereas it seems more subtly woven into the fabric of the Singapore Biennale. How do you react to the overall feeling that the East is the new West, that the world is shifting eastwards, specifically in terms of art and culture?

TBH: I believe it is simply about broadening the canvas of what we mean by art and art development. It is no longer a question of who came first and who came second. We have many presents and many contemporaries moving and occurring simultaneously. It is not useful any more to talk about where something originated. Do we care where installation started? No. It is completely irrelevant at this point in time. My response is this: all these biennials – Sharjah, Kochi, Singapore – combine to say that there are other trajectories, other contemporaries happening. Obviously, it doesn’t mean we deny the existence of the North. But we exist. Don’t ignore us.